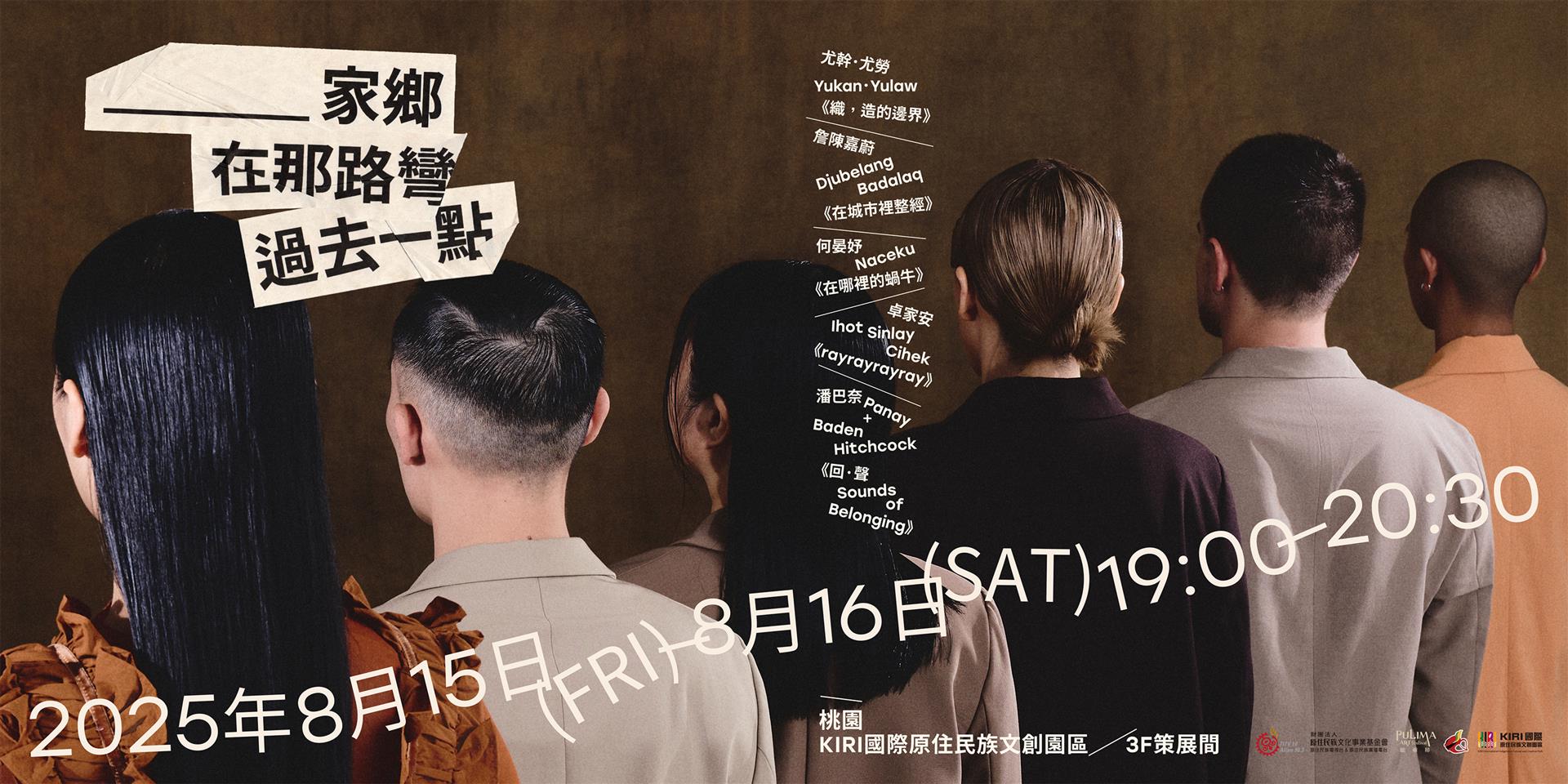

創作者介紹|【織作即介入】——以布料重織身份的城市行者

1993年出生於新北,現居高雄。母親為屏東獅子鄉排灣族人,父親為西門町閩南人。畢業於國立臺北藝術大學美術學院,為第二代都市原青,現為文化部文化資產局排灣族 tjemenun傳統織布第二屆傳習生。創作以影像、織布與刺繡為媒介,關注都市原民的生存經驗與文化記憶,探索族群與身份、自我認同與文化轉化的議題。其作品《在城市裡織作》(2016–)以織作行動回應都市與傳統的斷裂與延續,強調材料轉化與空間遷移中的文化再生;《Lau‧烙攝影計畫》(2017)則結合八位都市原青之影像書寫,共構當代原青群像;早期作品如《排漢公主》(2015)、《小玲的女兒》(2017)則透過自我影像與「他者的凝視」對話,探討「何謂原住民」的身份辯證。長期參與社會運動現場,關注轉型正義、同志權益與青年行動,2024年以織作與對話形式重啟《在城市裡織作》,將女性、青年、原住民與勞工等多重身份帶入街頭實踐,透過身體行動記錄現場故事,展現原住民藝術的跨域實踐與公共介入。其創作與評論見於《謬誌茗》、《ART Touch典藏》、《先躺在說》、《關鍵評論》、《玉蘭設計》等媒體。

節目名稱|《在城市裡整經——pinakaitan》織路之始:關於排灣整經歌 sa senayan

排灣織布,即是排灣族的敘事;織紋,即是文字。透過《整經歌》(sa senayan)的吟唱,我們搭建起一座排灣織女跨越時空、身心共感的路徑。在織布工序中,最為關鍵的一步稱為「qameljesai」——即「整經」。織女口中的 sa senayan,不僅是勞動時的吟唱,更是身體在空間中定位與移動的指引。千百條經線在整經柱間反覆穿梭,而不使織女迷途的祕訣,便在歌謠之中。只要唱對了歌,就走在對的路上。不同的織法,對應著不同的整經歌,從而創造出千變萬化的織紋。其中,最基礎的《平織整經歌》(pinakaitan sa senayan),更是建立排灣織女共同世界觀的基石:

kinizala a tjai vavau

gemu sulj ta tjai teku

valiqicen i ka navalj

cemikel sema ka viri

——Ljumiyang 許春美 老師所傳《平織整經歌》

此歌大意為:「上線,繞過 kinizala;下線,繞過 ginusulj;雙線同行,繞過 kanavalj交叉;折返,回到 kaviri。」織女們依此確認各經線與整經柱的相對位置與動作,循著前人走過的織路,窺見屬於排灣的世界與風景。

當代儀式:《在城市裡整經——pinakaitan》

前作《在城市裡織作》,是將織布作為文化宣告,在衝撞的社運現場,織出我族的存在。新作《在城市裡整經》,則選擇退入劇場此一象徵性的「黑盒子」,如回到 vuvu(祖輩)的 umaq(家)。在此,我不再僅是「被看見」,而是邀請觀者進入一場神聖儀式,「共同聆聽」織布前那最寧靜、最專注的準備時刻。劇場,成為了我在城市裡搭建的暫時性家屋。若說「織作」是寫下敘事,「整經」便是創造敘事的筆劃與結構。它是織布的靈魂與骨架,在圖紋顯現之前,已決定了所有故事的可能性。新作聚焦於「整經」,正是希望帶領觀者回到一切的源頭,去看見那些隱藏在華美織紋之下,更為根本、內在的文化秩序與宇宙觀。

在這場儀式行為中,我的身體即是檔案,聲音即是路徑。每一次彎腰、每一次穿線、每一句 sa senayan 的吟唱,皆非表演,而是跨時空身體記憶的再現。當代城市中的我,與部落家屋裡的織女,透過同一首歌、同一套動作,呼吸著同樣的氣息,確認著同一條路徑。觀者所見證的,將不僅是一位排灣藝術家,而是一條文化血脈的綿延與具象。

此次選擇最基礎的《平織整經歌》,並非因其簡單,而是因其根本。它是每一位排灣織女的起點,是我們共同世界觀的基石。在當代社會的喧囂與複雜中,回到「一上、一下」的純粹秩序裡,本身即是一種尋根的行動。它提醒著我們,無論世界如何變幻,那來自祖先的結構與智慧,永遠能作為我們安身立命的座標。

Artist Introduction — “Weaving as Intervention”: A City Wanderer Reweaving Identity Through Textiles

Born in 1993 in New Taipei City, Djubelang currently resides in Kaohsiung. Her mother is a Paiwan from Shizi Township, Pingtung County, and her father is a Minnan from the Ximending area. A graduate of the School of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts (TNUA), she is a second-generation urban Indigenous youth and currently part of the second cohort of apprentices in the “tjemenun” (traditional Paiwan weaving) training program run by the Bureau of Cultural Heritage, Ministry of Culture.

Her creative practice employs various media such as video, weaving, and embroidery to explore the lived experiences and cultural memories of urban Indigenous peoples. Her work interrogates themes of ethnicity and identity, self-recognition, and cultural transformation.

“Weaving in the City” (2016–) responds to the dialogue between discontinuities and continuities related to urban life and tradition through acts of weaving, emphasizing cultural regeneration through material transformation and spatial migration.

“Lau: A Photographic Imprint Project” (2017) is a collaborative visual narrative with eight urban Indigenous youths, constructing a collective portrait of contemporary Indigenous identity.

Earlier works such as “Pai-Han Princess” (2015) and “Daughter of Hsiao-Ling” (2017) engage in a dialogue between self-representation and the "gaze of others," critically examining what it means to be Indigenous in modern society.

Djubelang has long been active in social movements, focusing on transitional justice, LGBTQ+ rights, and youth activism. In 2024, she reopened the work “Weaving in the City” through acts of textile-making and dialogue, bringing intersectional identities—female, youth, Indigenous, and working-class—into the streets. Through embodied actions and storytelling, her work demonstrates the potential of Indigenous art as a form of cross-disciplinary practice and public intervention. Her creations and critical writing have been widely featured in Mummum Zine, ART Touch, Lie Down First, The News Lens, and Yulan Design.

Program Title: Warping in the City — pinakaitan-The Beginning of the Weaving Path: About the Paiwan Warping Song sa senayan

For the Paiwan people, weaving is a way to tell stories, and woven patterns serve as a written language. Through the chanting of the traditional warping song sa senayan, a path is built across time and space, connecting the bodies and spirits of Paiwan women weavers.

In the weaving process, one of the most important steps is called qameljesai, which means “warping.” The sa senayan sung by Paiwan women weavers is more than a chant to accompany labor—it is a guide for the body’s orientation and movement through space. As thousands of warp threads pass repeatedly between the warping poles, the secret to not losing one's way lies in the song. If the song is sung correctly, the path is followed correctly.

Different weaving techniques correspond to different warping songs, resulting in the richly diverse patterns of Paiwan textiles. Among them, the most fundamental is the plain weave warping song pinakaitan sa senayan, which forms the cornerstone of a shared worldview among Paiwan weavers:

kinizala a tjai vavau

gemu sulj ta tjai teku

valiqicen i ka navalj

cemikel sema ka viri

— taught by Ljumiyang (Hsu Chun-mei)

The meaning of the lyrics is as follows:

“Upper thread—pass through kinizala;

Lower thread—pass through ginusulj;

Double threads—cross at kanavalj;

Turn back—return to kaviri.”

By following these verses, weavers determine the position of each warp thread in relation to the warping poles. Through the rhythmic repetition of inherited gestures, they walk the path of their ancestors, revealing the universe of Paiwan culture.

Contemporary Ritual: Warping in the City — pinakaitan

Djubelang’s previous work, Weaving in the City, positioned weaving as a cultural declaration, asserting Paiwan presence amidst the turbulence of social movements. In contrast, her new work Warping in the City retreats into the symbolic “black box” of the theater—like returning to the umaq (home) of the vuvu (ancestors). Here, it is no longer about simply being “seen,” but about inviting the audience into a sacred ritual—one of “listening together” to the quietest and most focused moment before weaving begins. The theater becomes a temporary umaq that Djubelang constructs within the city.

If weaving is the act of writing a narrative, then warping is its structure—the strokes and framework beneath the patterns. It is the soul and skeleton of textile-making; before any pattern emerges, the warp already determines the possibilities of the story. By focusing on qameljesai, this new work seeks to lead the audience back to the source—to the hidden cultural logic and cosmology embedded in the warp.

In this ritual action, the artist’s body becomes an archive, and her voice becomes the path. Every bow, every threading motion, every chant of sa senayan is not a performance, but a reappearance of embodied memory across time and space. The urban artist and the weaver in the ancestral home breathe in unison, following the same gestures and guided by the same song. What the audience witnesses is not just a Paiwan artist, but a living continuity—an embodiment of cultural lineage.

The decision to work with the foundational “plain weave warping song” is not due to its simplicity, but because it represents the origin. It is the starting point for all Paiwan weavers and the cornerstone of a shared worldview. In the noise and complexity of contemporary life, returning to the simple rhythm of “up and down” is itself an act of returning to one’s roots. It reminds us that, no matter how the world changes, the structures and wisdom passed down from our ancestors remain a constant compass for who we are.

延伸閱讀:

➤ 專訪|詹陳嘉蔚 Djubelang Badalaq